GMS2 Multiplayer: A Simple WebSocket Relay Architecture Guide

Nov 30, 2025

1. Introduction: The "Postman" Philosophy

When we think about multiplayer, our minds often jump to massive, authoritative servers that calculate physics, prevent cheating, and simulate a whole world. That’s a mountain to climb. But for many turn-based or grid-based games, you don't need a God; you just need a Postman.

The architecture I’m outlining here is a Relay Server model. The server’s job isn't to decide if a move is legal; its job is to manage the "mail." It handles:

- Connections: Who is currently online?

- Room Management: Creating private spaces for two players to talk.

- Broadcasting: Taking a message from Player A and delivering it to Player B.

By offloading the game logic to the clients and using the server strictly as a switchboard, we can get a Node.js backend up and running in a few dozen lines of code, and GameMaker Studio 2 (GMS2) can treat a remote opponent almost exactly like a local one.

2. Background: The L-Game Case Study

To make this concrete, let's look at my implementation of L-Game. If you haven't played it, it's a deceptively simple strategy game played on a 4 4 grid. Players move an L-shaped piece (attack) and then optionally move a neutral coin (defense) to block their opponent.

Check it out: You can try the game here or read more about the Game Juice and polish here

The "Abstract Player" Pattern

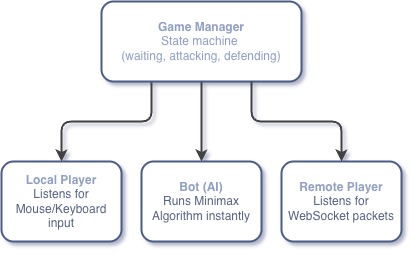

The secret to making multiplayer easy in G MS2 is how you structure your objects. In L-Game, I don't hardcode "Player 1" and "Player 2." Instead, I use a Game Manager that controls the state machine (waiting, attacking, defending) and communicates with two Abstract Player objects.

The Game Manager doesn't care what is controlling those players. This allows for a beautiful abstraction:

- Local Player: Acts as a bridge for Hardware Input. It listens for mouse or keyboard events during the "Attack" or "Defense" phases and translates those signals into game coordinates.

- Bot: Acts as a bridge for Calculated Logic. Instead of waiting for a click, it runs a search algorithm to select a move and submits it to the Manager in the exact same format as a human player.

- Remote Player: Bridges Network Data. It remains idle until the GMS2 Networking Async event receives a WebSocket packet from our server. It then unpacks the data and execute that player's move.

3. The Handshake & Room Logic

With the player objects ready, the Node.js server (our Postman) needs to pair them up. THis is handled via a simple Room System:

- The Dispatch: The process begins when the Host sends their game settings - for example,

host:red_first. This tells the server, "I'm opening a room, and in this match, the Red player goes first." - The Token Exchange: The server generates a unique Token (like

881) and sends it back to the Host. The server now stores that room 881 belongs to this Host (via a socket connection) and uses thered_firstrule. - The Join Request: The Guest enters the code

881. The server looks through its active rooms and finds the match. - The Pairing: This is the final confirmation that syncs both players:

- To the Guest: The server sends

paired:red_first. Now the Guest's game knows exactly which player is starting without the user having to select it manually. - To the Host: The server sends a simple

paired:. This acts as a "Green Light" to move from the lobby to the game board.

- To the Guest: The server sends

This Postman approach is simple as:

- Zero Game Knowledge: Notice that the server doesn't care what

red_firstmeans. It just stores the string and hands it to the Guest. You can add logics and the server code stays exactly the same. - Synchronized State: By passing the config during the handshake, you ensure that both players are looking at the same game rules before the game starts.

4. The Active Game Loop: Command & Relay

Once the handshake is complete, the server’s role becomes beautifully simple. It stops being a "Matchmaker" and starts being a Relay. I call this the "Postman" phase: the server doesn't care what is inside your messages; it only cares who they are addressed to.

The Postman's Simple Job

In our Node.js code, this is handled by a simple logic gate. If a message starts with command:, the server looks at its pairs map, finds the connected opponent, and forwards the data.

- No Logic on Server: The server doesn't know the rules of the L-Game. It doesn't know what an "Attack" is or if a move is legal.

- Transparent Tunnel: It simply strips the

command:prefix and pushes the raw instructions to the other side.Trade-offs: Because the server is "blind" and doesn't validate moves, it relies entirely on the honesty of the clients. This model is best for friendly matches or low-stakes games, as a malicious user could theoretically send a fake

command:string that the server would faithfully deliver or mishandle. Also, if a single packet containing a move is lost, the two games will fall out of sync. Therefore, a periodic State Sync should also be implemented to perform an anti-desync.

The Sequence of a Move

To visualize how a turn works, let's look at the sequence of a single move (an Attack followed by a Defense):

- Dispatch: Player 1 decides on a move. Their game sends

command:attack:0_1_2. - The Relay: The Server sees the

command:tag, finds Player 2, and sendsthem attack:0_1_2. - Execution: Player 2’s game receives the string, parses the coordinates, and moves the L-piece on their screen.

- Acknowledgment: Player 2 sends back

command:received:. The Server relays this asreceived:to Player 1, confirming the "letter" was delivered. - The Second Half: Player 1 then sends the defense move (e.g.,

command:defend:1_1_3_2), which follows the exact same relay path.

Why This Matters

This "blind relay" approach is incredibly powerful for simple game development. Because the server is just a middleman:

- You can update your game (change coordinates, add new pieces, or change the rules) without ever touching your Node.js code.

- Latency is minimized because the server isn't wasting time processing game logic; it's just moving strings from Point A to Point B.

5.Connecting the Dots: GMS2 Integration

We have the server (the Postman) and the protocol (the Mail). Now we need to bridge the gap in GameMaker Studio 2. This happens in two stages: establishing the connection and handling the incoming data stream

Step 1: Opening the Mailbox

Before any messages can be sent, we must establish a persistent connection to our Node.js server. In GMS2, we use a raw WebSocket socket. This is usually triggered when the player clicks "Host" or "Join" in your menu.

// Initializing the Connection

global.ws = network_create_socket(network_socket_ws);

var result = network_connect_raw_async(global.ws, global.SOCKET_SERVER, global.SOCKET_PORT);

if (result < 0) {

show_debug_message("Connection failed!");

}

network_socket_ws: This tells GMS2 to use the WebSocket protocol, which is exactly what our Node.js server is listening for.network_connect_raw_async: This is crucial. It prevents the game from "freezing" while it waits for the server to respond.

Step 2: Processing the Delivery

To wrap up the technical implementation, let's look at how the GMS2 Networking Async Event actually processes the data. We can break this down into three layers: the Listener, the Distributor, and the Execution.

Layer 1: The listener

Everything starts by identifying the message. Since GMS2 can handle multiple network events at once, we first ensure we are only listening to our specific WebSocket.

var sid = async_load[? "id"];

if (sid == global.ws) {

var stype = async_load[? "type"];

// This is where the branching logic begins...

}

Layer 2: The Distributor (stype)

Now we look at the nature of the event. Is it a new connection, or is it actual data being delivered?

network_type_non_blocking_connect: This triggers once when you first hit the server. This is your "Introduction" phase where the Host tells the server what the game rules are (e.g.,host:green_first), or the Client submits a token to join.network_type_data: This is the core of the game loop. It triggers every time the Postman delivers a packet.network_type_disconnect: The cleanup phase. If this triggers, we reset the UI and variables because the connection to the Postman has been severed.

Layer 3: The Deep Dive (Processing Data)

When stype is network_type_data, we dig into the buffer to read the data inside. This is where our protocol executes.

- Read the Buffer: We convert raw binary data back into readable string (e.g.,

attack:0_1_2).var r_buffer = async_load[? "buffer"]; var msg = buffer_read(r_buffer, buffer_string); - Extract the Command: Using a parser, we separate the string into command and its value.

var data = { command: "", value: "" }; scr_extract_message(msg, data); // Extract command and value from the message - The Switch: Finally, we handle the logic based on the

data.commandextracted. This is where the game reacts to the server's instructions.switch(data.command) { // This is where the game logic begins... }

By nesting the logic this way, you keep your game organized. The "outer" layers handle the boring network stuff (connecting/disconnecting), while the "inner" layers focus purely on the L-Game's unique mechanics.

6. Conclusion

We've reached the end of our Simple WebSocket Relay journey. By treating the server as a logic-less middleman, we’ve bypassed the most intimidating part of multiplayer development: authoritative server logic.

However, while the "Postman" makes the networking simple, the burden of State Management now sits squarely on your GameMaker project. A robust multiplayer session is more than just sending coordinates; it’s about handling the "What Ifs."

The Critical Case Checklist

Even with a perfect relay, you must ensure your GMS2 client handles these tedious but vital scenarios:

- Disconnects: What happens if a player’s internet cuts out mid-move? Your unpaired logic must be bulletproof to prevent the remaining player from being stuck in a permanent "Waiting for Opponent" state.

- Memory Management: When a session ends, are you resetting your

globalvariables and clearing your buffers? Failing to clean up leads to "Ghost Games" where data from the last match leaks into the next one. - Mode Switching: This is the most critical part of the Abstract Player pattern. If a player switches from a Multiplayer match to a Single-player session, you must ensure the game correctly destroys the Remote Player and replaces it with a Bot or Local instance.

- State Resync (Anti-Desync): In a "blind relay," if a single packet containing a move is lost, the two game clients will fall out of sync. You should implement a periodic State Sync where the host sends the entire board state string. Upon receipt, the guest overwrites their local variables to match the host exactly.

Building a multiplayer game isn't just about the technology - it’s about consistency. The Postman ensures the mail gets delivered, but it’s up to your GameMaker code to ensure the right Brain is active to process it.

Happy coding!

( ´ ▽ ` )

Join the discussion!